America’s quest to reclaim leadership in chipmaking has a new plot twist. For years, the most important machine on any cutting edge fab floor has been the lithography scanner that writes circuit blueprints onto pristine silicon. Today that title is owned by Extreme Ultraviolet lithography, the EUV workhorse with a 13.5 nm wavelength that lets manufacturers print the tiny, tightly packed features required for modern logic.

When an application processor at the 3 nm class squeezes in 20 to 30 billion transistors or even more, the only way to draw those dense, intricate patterns reliably is with light this short and optics this precise.

EUV did not arrive in a vacuum. It followed Deep Ultraviolet tools using 193 nm light that shepherded the industry through 28 nm and 14 nm down toward the 10 nm era. But the physics demanded a new regime. Shorter wavelength means smaller minimum feature size and less diffraction blur, allowing designers to place more transistors per square millimeter. That density translates directly into performance per watt: faster chips that sip rather than gulp electricity, a requirement for everything from hyperscale data centers to battery powered phones.

There is a monumental price tag attached. A state of the art Low NA EUV system typically lives in the 150 to 200 million dollar range, reflecting the exotic engineering that includes a tin droplet plasma light source, ultrapure mirrors, vibration killing stages, and a cleanroom environment straight out of science fiction. The next leap is already here in the form of High NA EUV with a numerical aperture around 0.55 versus roughly 0.33 for prior tools. Higher NA increases the angle at which light enters the optics, boosting resolution and enabling even smaller features with tighter line edge control. Those scanners command roughly 350 to 380 million dollars each before you even count installation, service, and the ecosystem of masks, resists, and metrology that must keep pace.

Why does High NA matter so much? Without it, fabs are forced to resort to aggressive multipatterning. The layout is split into several exposures that must be perfectly aligned and repeated, raising cycle time, power consumption, and the risk of overlay errors that slash yield. More steps also mean more reticle wear, more pellicle challenges, and more opportunities for stochastic defects to creep into critical paths. In short, it works, but at a punishing economic and technical cost as feature sizes shrink again.

There is another crucial reality: only one company builds EUV scanners at scale. The Netherlands based ASML is the sole supplier, and the company is deeply entangled in geopolitics. Export controls have limited where its most advanced tools can ship, reshaping national strategies and forcing fabs and governments to think hard about domestic capacity, resilience, and technology access. In that context, any credible alternative to the EUV monopoly is newsworthy on both technical and strategic grounds.

Enter Substrate, a U.S. startup betting on X ray lithography powered by compact particle accelerators. The concept is bold. Instead of generating 13.5 nm light and bouncing it through a delicate mirror system, Substrate proposes to accelerate charged particles to near light speeds and convert that energy into an illumination beam billions of times brighter than the sun at the tool plane. The company’s pitch is straightforward yet ambitious: match the resolution needed for 2 nm class processes and push beyond, while lowering operating costs and simplifying the optical stack by using newly designed optics and high speed mechanics tailored for X rays.

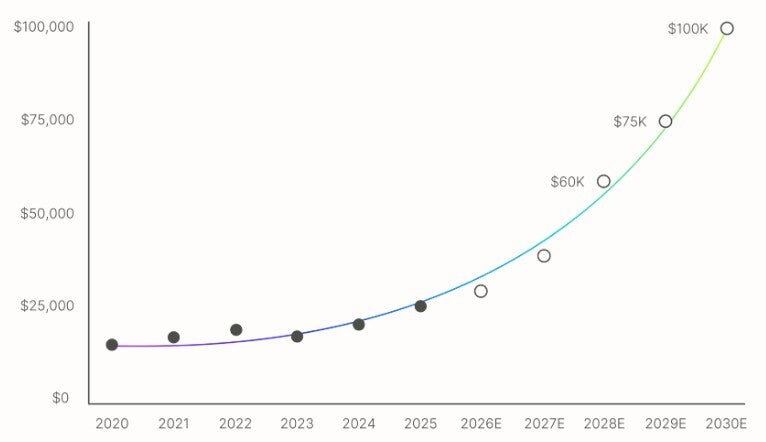

If successful, that could stretch Moore’s Law further. Gordon Moore’s observation about transistor density doubling roughly every two years has never been a law of nature, only a target the industry repeatedly hit through ingenuity. As we close in on atomic scales, progress is as much about economics as physics. Rock’s Law adds the sobering counterpoint: the cost of a leading edge fab roughly doubles every four years. Ten years ago, a top tier facility might have demanded on the order of five billion dollars. Today, greenlighting a flagship fab commonly means tens of billions, and that is before counting the ongoing expense of tools, utilities, and skilled staff.

Substrate frames the next half decade in stark terms. By 2030, the company argues, the all in cost per wafer at the cutting edge could reach 100 thousand dollars if the industry keeps leaning on ever more complex multipatterning and scarcity priced tools. At those levels, only a handful of giants would be able to afford to design or manufacture chips on the newest nodes. The physics may still allow scaling, but the spreadsheet says otherwise. That is the cliff the startup wants to avoid, promising a pathway to push leading edge wafers toward a cost closer to ten thousand dollars by the end of the decade.

How might X ray lithography change the equation? In principle, shorter effective wavelengths and different illumination geometries can reduce mask complexity and cut the number of exposures. Fewer steps mean fewer chances for misalignment and stochastic variation, with potential benefits for yield and cycle time. A brighter, more controllable source could also enable faster scanning speeds, improving throughput. But the shift is not trivial. X rays interact with matter differently from EUV, so resists must be reimagined for sensitivity and line edge roughness. Mask technology, heat management, and in tool metrology all require fresh solutions. Every promise comes with a to do list measured in patents, prototypes, and process integration sprints.

Even with those caveats, the timing is intriguing. The United States is already investing through industrial policy and incentives to expand domestic manufacturing capacity and onshore essential supply chains. An approach that lessens dependence on a single foreign supplier, while attacking the cost spiral that threatens Moore’s Law, aligns with both economic and national security goals. If Substrate can deliver reliable, fab proven tools that meet or exceed 2 nm class requirements and plug into standard semiconductor workflows, the ripple effects would be enormous.

A realistic outlook must also acknowledge inertia. ASML’s High NA EUV is here, qualified step by step, supported by a mature photoresist ecosystem, and backed by top foundries that have spent years mastering EUV stochastics and defect control. Any challenger must clear a very high bar on uptime, overlay, critical dimension uniformity, pellicle or mask strategy, and total cost of ownership. Fabs will run exhaustive pilots before shifting volume products. The winner will be the technology that consistently hits yield targets at the lowest cost per good die, not the one with the most dazzling physics demo.

Still, the upside is compelling. Imagine leading edge silicon that is not the exclusive province of a few deep pocketed players but a platform accessible to a wider field of designers. More competition at the process frontier could accelerate innovation in AI accelerators, edge compute, 6G radios, quantum control electronics, and energy efficient data center silicon. That is the vision behind the headlines: not merely a new light source, but a reset of the cost structure that determines who gets to play at the top of the node stack.

Whether the future is incremental with High NA EUV or disruptive with accelerator driven X ray systems, the stakes are the same. Keep scaling, keep improving performance per watt, and keep pushing down the cost of computation, or watch the economics stall progress. Substrate’s claim to extend Moore’s Law while bending Rock’s Law is audacious, and it will require hard engineering, rigorous validation, and industrial scale partnerships. If it works, though, it could help return U.S. chipmaking to a position of genuine leadership, not just in rhetoric but in the daily cadence of wafers in and wafers out.