NVIDIA’s Rubin generation has crossed the line from lab demo to factory reality. According to reports out of Taiwan, the company has begun running Rubin GPUs down early production lines while simultaneously locking in HBM4 memory samples from every major DRAM supplier.

That two-track milestone – silicon in flow and next-gen memory in hand – signals that Jensen Huang’s roadmap is pacing ahead of an AI market that refuses to tap the brakes.

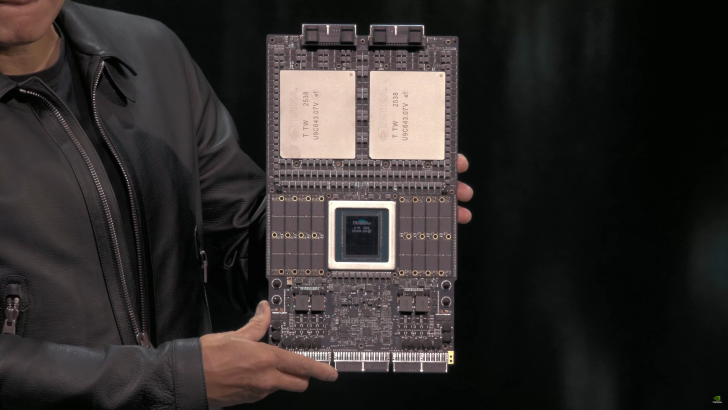

The public first glimpse came weeks earlier at GTC 2025 in Washington, where NVIDIA showed a Vera Rubin Superchip: two colossal GPUs paired with the next-gen Vera CPU, ringed by banks of LPDDR for control and I/O. It wasn’t a gaming board dressed up for the data center. It was a purpose-built accelerator designed for model training and inference at the scale cloud providers actually deploy. That distinction – compute first, not frames per second – matters for expectations and timelines.

Risk vs. Mass Production (and why that nuance matters)

Much of the online chatter trips over a simple manufacturing truth: risk production is not mass production. Risk runs are controlled volumes that validate process corners, yield curves, reticle revisions, and packaging recipes before the floodgates open. Mass production is when a product is released to sustained, high-throughput manufacturing with stable yields and predictable ship dates. For Rubin, the industry guidance remains mass production around Q3 2026 (or earlier if yields and supply chain orchestration cooperate). Today’s “entering production line” language describes that transition from first silicon and bring-up toward repeatable builds – not trucks leaving fabs by the tens of thousands.

HBM4: multi-vendor by design

NVIDIA has always hedged memory supply by qualifying multiple DRAM partners. With HBM4 slated to accompany Rubin, that strategy becomes existential. AI accelerators are fundamentally bandwidth devices; starve the GPU of memory throughput and your petaflops turn into paper tigers. Securing HBM4 samples from every tier-one supplier early lets NVIDIA tune power curves, thermals, and signal integrity across vendors, then mix and match capacity to demand. It also reduces the risk that any one supplier’s hiccup kneecaps an entire product cycle.

TSMC’s 3nm ramp and Jensen’s wafer appetite

The other piece snapping into place is foundry throughput. TSMC has reportedly stepped up 3nm capacity to meet the Blackwell deluge and get ahead of Rubin. Company leadership is coy about exact wafer counts (unsurprisingly), but the signal is clear: NVIDIA is buying as much advanced capacity as it can responsibly absorb. That doesn’t just mean GPUs; the company is simultaneously taping out CPUs, networking silicon, DPUs, and switches that feed the same AI datacenter flywheel. When the pipeline is this wide, coordination across dies, interposers, and advanced packaging becomes as strategic as the chips themselves.

Compute now, consumer later

One recurring community question: what about gaming? Rubin, as discussed, is an accelerator platform. The parts paraded on stage and now entering lines are built for data centers – matrix engines, interconnect fabric, and memory bandwidth take precedence over the raster/RT front-end that excites gamers. Expect consumer derivatives to follow only once the datacenter variant is de-risked and supply stabilizes. That cadence, paired with ongoing demand for Blackwell and potential mid-cycle refreshes, is why many analysts caution that desktop “6000-series” talk remains speculative until late 2026 at best – and 2027 isn’t outlandish depending on foundry mix and packaging availability.

Thermals, power, and the meme vs. the math

Yes, the internet jokes about molten GPUs and “over 9000” power budgets. Reality: power targets scale with performance and are constrained by rack density, liquid cooling, and TCO models that cloud buyers quantify to the decimal. Rubin won’t be immune to heat; nothing at this scale is. But the thermal design conversation has moved from “can we cool it?” to “what cooling delivers lowest total cost per trained token?” That’s why you see relentless investment in cold plates, immersion options, and facility retrofits – because performance per watt and watts per rack are now procurement levers, not afterthoughts.

OpenAI, hyperscalers – and the stakes

Rubin’s name has already been attached in reporting to eye-watering cloud commitments, including a reported mega-deal with OpenAI. Whether or not every rumored dollar materializes, the vector is obvious: next-gen accelerators will be allocated first to the customers who can stand up fleets quickly and keep them fed with data, power, and workloads. That triage is another reason consumer timelines may stretch: opportunity cost is simply higher in AI right now.

AMD, Samsung, and competitive counter-moves

AMD’s roadmap will inevitably meet Rubin in the field, and there’s growing speculation about RDNA and CDNA trajectories, foundry nodes, and a potential Samsung 2nm angle for future gaming parts. Skepticism about core counts and head-to-head matchups is healthy; what matters is system-level performance – software stacks, memory bandwidth, compiler maturity, and cluster-scale networking. NVIDIA still enjoys an ecosystem advantage, but competition tends to accelerate everyone’s best ideas.

Bottom line

Rubin touching production lines while HBM4 samples arrive from all majors is the clearest sign yet that NVIDIA intends to compress the distance between architectures. Blackwell demand remains ferocious; Rubin is already queuing behind it. If you’re a datacenter buyer, start modeling bandwidth tiers and cooling footprints now. If you’re a gamer, calibrate expectations: Rubin’s first act belongs to AI. The second will come – just on the industry’s clock, not the meme’s.

1 comment

PSA: risk production ≠ volume. Mass in 2026 Q3 checks out for me