Nvidia’s long and messy breakup with the Chinese data center market just got an unexpected sequel. After months of telling investors that its China data center business had effectively been written down to zero because of tightening United States export controls, the GPU giant has now been told it can once again ship Hopper based H200 accelerators into the mainland. The approval, announced via Donald Trump’s social platform and framed as a way to tax high end AI chips heading to China, sounds on the surface like a dramatic reopening.

In reality it looks more like a narrow side door, guarded by tariffs, politics and increasingly capable local rivals.

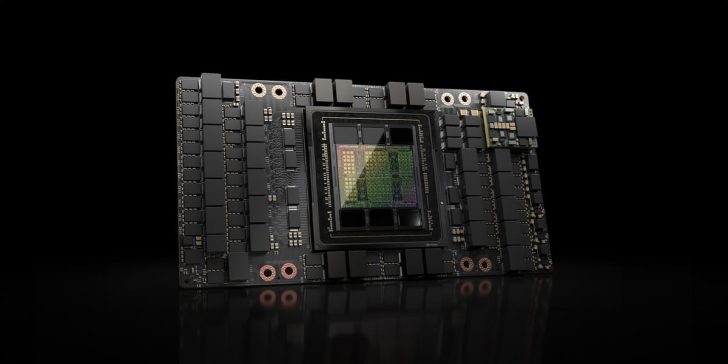

For years China was one of Nvidia’s most important overseas markets for data center GPUs, powering recommendation engines, cloud platforms and the early generations of large language models for companies like Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent. That boom was abruptly interrupted as Washington expanded its export rules, first cutting off flagship accelerators such as A100 and H100, then pushing Nvidia to design special downclocked versions like A800, H800 and H20 that slipped just under freshly drawn performance thresholds. Even those compromises were eventually swept away by stricter controls. Jensen Huang responded by warning that trying to freeze Chinese progress was bad industrial strategy and by telling shareholders that Nvidia’s data center revenue from China had been largely erased.

The newly granted licence for Hopper H200 does not undo that journey so much as bolt a complicated footnote onto it. Under the latest framework, Nvidia is allowed to sell H200 accelerators into China but must hand over a 25 percent cut on every unit, a de facto export levy layered on top of already eye watering prices. Commentators following the saga have jokingly described it as a tribute collected on each GPU. Nvidia can either keep prices steady and watch margins shrink or mark H200 up even further and ask Chinese customers to shoulder the extra cost. Either way the card becomes a harder sell in a market that has spent the past two years racing to reduce its dependency on United States silicon.

That is one reason many Chinese firms are expected to greet the news with a shrug. Another is that Beijing has been steadily rewriting the procurement rulebook for its own data centers. Guidance for government agencies, state owned enterprises and any cloud provider that relies on public contracts increasingly steers new clusters toward domestic accelerators. Industry chatter describes tender documents where any bid listing Nvidia, AMD or Intel GPUs for inference work is automatically disqualified. Against that backdrop the sudden green light out of Washington looks, to some investors, like a classic too little too late moment. Meme filled trading chats are already mocking the move as the United States begging to sell hardware that Chinese regulators and planners have decided no longer fits their long term strategy.

China has not stood still while export lawyers argued over clock speeds and chip to chip bandwidth. Huawei’s Ascend 910B and 910C accelerators, along with products from designers such as Cambricon, are being pushed as home grown answers to Nvidia’s Hopper family. Promotional materials and selective benchmarks routinely claim H100 class or better performance in specific workloads. At the same time the broader ecosystem is being rebuilt around the idea of technological sovereignty, from domestic operating systems and cloud stacks to home grown frameworks that can, in theory, replace PyTorch and TensorFlow pipelines built on foreign foundations. For Beijing this is not only about training chatbots; it is about controlling the full stack that underpins finance, cloud, telecoms and surveillance. In that context importing another generation of expensive United States GPUs at a premium looks like a tactical stopgap at best rather than a cornerstone of policy.

Yet Nvidia retains one formidable advantage that even the most enthusiastic domestic chip champions cannot ignore: software. Years of investment in CUDA, cuDNN and an entire ecosystem of libraries, compilers and debugging tools have created a de facto standard stack for modern AI research and deployment. Reports from Chinese labs and start ups often describe migrating large models onto local accelerators as painful, with patchy drivers, immature toolchains and missing equivalents for many CUDA centric workflows. Teams complain about spending months rewriting kernels, hunting obscure bugs and dealing with inconsistent performance. Some have chosen to rent offshore cloud capacity rather than rebuild everything around young domestic platforms. That is where H200 could still carve out a niche. For firms that are not bound by the strictest procurement rules, paying more for Nvidia hardware may still be cheaper than rearchitecting every training pipeline from scratch.

The politics, however, are only getting more tangled. When rumours first surfaced that a cut down H200 variant might be offered to Chinese customers, Jensen Huang publicly stressed that China would not accept a product that failed to meet its performance needs. Fast forward and Nvidia now finds itself in a world where Washington is authorising sales while Beijing tightens the door from its side and online commenters joke that Xi simply does not want Jensen’s overpriced cards anymore. Seen from that angle, the 25 percent levy looks less like a clever way to recoup lost corporate taxes and more like a face saving gesture in a power struggle where both governments are comfortable using private companies as tools of statecraft.

Crucially the approval applies only to Hopper. The next generation Blackwell and Rubin architectures, which promise another major leap in performance, memory bandwidth and efficiency, remain off the table for China under the current stance. AMD is reported to have secured similar carve outs for certain accelerators, but those also sit behind strict performance and customer guardrails. The message from Washington is blunt: Chinese firms may, in tightly controlled circumstances, buy slightly detuned versions of yesterday’s chips, but they will not be trusted with tomorrow’s. Markets have already started to price in that nuance. Short lived rallies on headlines about relaxed exports have been followed by sharp pullbacks once the fine print emerges, leaving traders posting screenshots of wiped out gains and arguing over whether the China story still deserves a premium in Nvidia’s valuation.

The broader conversation around the H200 decision reaches far beyond one company’s earnings call. Critics across the spectrum argue that the AI chip war has laid bare how closely state power and private capital are intertwined, in Washington as much as in Beijing. Some see the new export tribute as a clumsy patch for decades of eroded corporate tax rates, shifting the fiscal burden in opaque ways instead of simply restoring a more balanced tax system at home. Others worry that turning individual chip licences into instruments of foreign policy will accelerate efforts in China and across the wider Global South to build their own semiconductor stacks, fragmenting what used to be a relatively integrated global market for high end compute.

For Nvidia, the path back into China now looks narrow, expensive and politically fragile. Hopper H200 shipments, even if they materialise at scale, are unlikely to recreate the free spending CUDA first boom that defined the pre sanctions era. Domestic accelerators are improving, procurement rules are hardening and the most advanced Blackwell based platforms are explicitly banned from the market. At the same time Chinese firms still wrestle with gaps in their software ecosystems, and many engineers remain deeply invested in Nvidia’s tools and know how. That tension ensures that H200 approval is not meaningless, but it is also far from a decisive victory. It is better understood as one move in a long running contest where raw silicon performance, developer mindshare and nationalist politics all collide. In that contest nobody is fully in control, and both sides are discovering just how expensive technological independence can become.