NVIDIA’s DGX Spark has been marketed first and foremost as a tiny AI supercomputer, a box you drop on your desk to chew through language models and vision workloads rather than to grind through games. Yet once you put consumer curiosity and a copy of Cyberpunk 2077 in the same room, the ending is almost inevitable: people are going to try to game on it. The surprise is not that it runs games at all, but that it can push path-traced Night City at triple-digit frame rates, so long as you are willing to lean heavily on DLSS 4 and Multi-Frame Generation (MFG).

That combination turns a compact AI workstation into something that behaves, in the right conditions, like a high-end gaming rig – and also reopens the old argument about what “real” FPS actually means.

DGX Spark systems are built by various OEMs, including NVIDIA itself, and they are not cheap toys. The most affordable configurations hover a little above the three-thousand-dollar mark, a noticeable discount from the original four-thousand-dollar launch price but still a long way from mainstream gaming PCs. You are paying for an AI appliance first: a quiet, dense box designed to sit in a lab, server rack, or production studio, not under a teenager’s desk. That context matters when people joke online about this being a “$3K console” – nobody at NVIDIA pretends this is a value play for gamers, even if the hardware is now being pushed in that direction by the community.

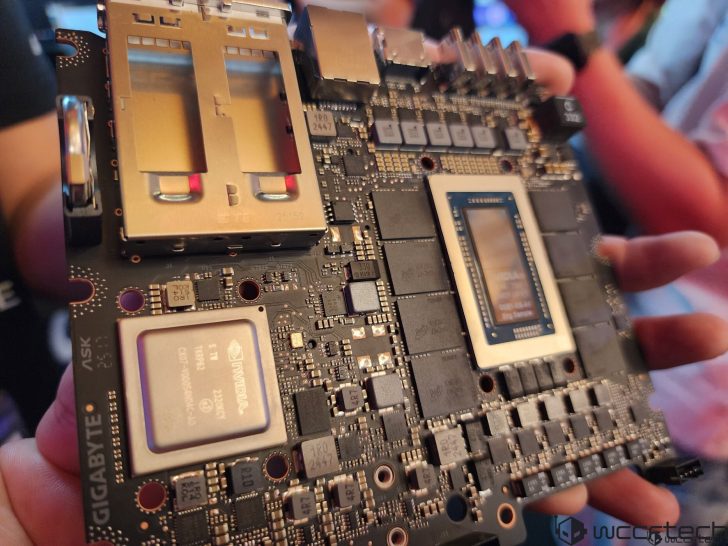

At the heart of each DGX Spark sits the GB10 Superchip, a compact slice of silicon that crams in both CPU and GPU logic. On the CPU side you get twenty ARM cores, tuned for efficiency and parallel workloads, while the graphics portion is based on the Blackwell architecture with 6144 CUDA cores. It is an SoC, not a traditional separate CPU plus graphics card, and it is fed by 128 GB of LPDDR5X memory running across a 273 GB/s bus. That memory is slower than the GDDR used on desktop cards, but there is far more of it available to the GPU than the 12 GB on a typical GeForce RTX 5070, and for AI workloads and larger games that shared pool is a big deal. The whole package is rated at around 140 watts, which is modest in GPU terms but substantial once you remember it covers CPU, GPU, and memory in a relatively tight thermal envelope.

On paper, the graphics block mirrors the CUDA core count of an RTX 5070 and tempts people into one-to-one comparisons. In reality, that is misleading. The GB10’s GPU runs in a stricter power budget, shares its memory pool with the CPU, and is enclosed in a miniature chassis with far less airflow than an open-air desktop tower. You are effectively dealing with an APU-style chip that happens to speak CUDA and Blackwell, not a drop-in replacement for a discrete gaming board. That distinction is important when we later talk about frame rates, because some of the community backlash stems from trying to read those numbers like they came from a standard gaming card when they really did not.

Before you ever see a frame of Cyberpunk, there is the small matter of getting a Windows-centric, x86-only, ray-traced behemoth to run properly on an ARM-based Linux environment. DGX Spark uses NVIDIA’s DGX OS, and out of the box it is geared towards containers, Python environments, and AI frameworks, not Steam libraries. To bridge the gap, NVIDIA engineers put together a relatively streamlined path using a combination of an automated FEX installer for arm64 and Valve’s Proton compatibility layer. In short, you pull down a helper script that wires up FEX and Steam on Ubuntu for ARM, launch Steam through FEXBash, install Cyberpunk 2077, and then force the game to use Proton 10.0-2 (beta) in the compatibility options. Once that is done, you can enable ray tracing, DLSS 4, and Multi-Frame Generation in the in-game graphics menu, run the built-in benchmark, and – critically – restart the game after toggling frame generation or ray tracing so the settings actually apply.

Earlier experiments with DGX Spark gaming painted a very different picture. Users who brute-forced their way through the Linux and ARM hurdles reported something in the region of 50 FPS at 1080p using medium settings, with ray tracing and DLSS disabled or partially broken. It proved that the machine could render Night City, but it was nowhere near the kind of premium experience people expect from a multi-thousand-dollar box. With the refined configuration described by NVIDIA’s own guide, the numbers are transformed: the system can now push more than 175 frames per second in the benchmark with Cyberpunk’s overall preset set to high, ray tracing cranked to Ultra (full path tracing), and DLSS 4 MFG turned on. Going from 50 to 175 FPS in the same title is not a small uplift – it is a different class of experience, at least on paper.

However, those eye-catching numbers come with a giant asterisk that seasoned readers instantly jumped on. DLSS 4’s Multi-Frame Generation works by inserting AI-generated frames in between traditionally rendered ones. If your base rendering rate is, say, 45 to 50 FPS and MFG is adding three synthetic frames for every real one, the counter might show 180 to 200 FPS while your “true” frames remain around that original 50. Latency and motion fluidity can still improve compared to plain 50 FPS thanks to techniques like NVIDIA Reflex, but purists argue – loudly – that this is not comparable to a native 180 FPS output. That is why online discussions around the DGX Spark benchmark are full of comments along the lines of “solid 1/4 real frames,” “nobody cares about FPS with MFG, show the numbers without frame-gen,” or “50 FPS ×4, pure cancer.” The passion behind those reactions is less about this specific box and more about a growing unease with the way modern upscaling and frame-generation technologies blur what performance metrics actually represent.

For extra context, NVIDIA’s tiny AI box is being pitted against AMD’s upcoming and existing APU-style solutions such as Strix Halo. In similar Cyberpunk scenarios at 1080p with high settings, the Strix Halo SoC has been shown reaching around 90 FPS when using FSR 3’s frame generation without ray tracing enabled. Once ray tracing is turned up to a high preset, even with frame-gen active, that figure can drop to roughly 40–50 FPS. Against that backdrop, DGX Spark’s 175-plus FPS result – even if driven strongly by MFG – looks very competitive for an integrated solution running under a strict 140-watt ceiling. AMD loyalists worry that this is a preview of NVIDIA marching into the APU and compact desktop market with aggressive AI-first chips, while NVIDIA sceptics dismiss the whole thing as “sponsored marketing” or “another Ngreedia stunt” built on synthetic frames and careful cherry-picking of tests.

Thermals and acoustics naturally come up when people imagine pushing a mini PC that hard, and the memes follow quickly: jokes about having to “just put a fan around it,” screenshots of hot-running cards, and sarcastic remarks that even NVIDIA admits its own designs can be a handful to cool. In practice, the 140 W envelope and the relatively low-clocked, efficiency-focused ARM cores mean DGX Spark is not the kind of fire-breathing monster that will melt your desk, but sustained path-traced gaming is still a very different load pattern than spiky AI inference jobs. Long-term testing will be needed to see whether these machines can maintain that 175-FPS-with-MFG experience over hours of real gameplay without throttling, especially in warmer rooms or minimalist office setups.

Looking ahead, the most intriguing part of DGX Spark may not be this one benchmark, but what it implies. The GB10 Superchip already blurs the line between AI accelerator and gaming silicon, and NVIDIA is almost certainly going to refine both the hardware and software stack in future revisions. Better drivers, more mature ARM gaming compatibility layers, and further DLSS and MFG optimizations could squeeze noticeably more out of the same silicon. At the same time, community pressure is mounting for transparent reporting of both “native” and “frame-gen” frame rates so people can decide for themselves whether quarter-real frames are worth the visual and latency trade-offs. For studios, researchers, and enthusiasts who want a single compact system that can train models by day and blast through neon-lit role-playing games by night, DGX Spark is an early, slightly chaotic glimpse of that converged future.

In short, NVIDIA’s AI mini PC has proven that it can be more than an inference box, but only if you are comfortable living in the modern, messy world of upscalers, reconstruction, and generated frames. The raw silicon inside the DGX Spark is impressive, the engineering that gets an x86 blockbuster running on ARM Linux is clever, and the performance numbers – even with all caveats – are undeniably eye-catching. Whether you view it as a genuine gaming milestone or as marketing bait propped up by AI-hallucinated frames says more about your tolerance for modern rendering tricks than about the hardware itself. Either way, the message is clear: the next wave of “AI supercomputers” will not politely stay in their own lane. They are coming for your games as well.