Hideo Kojima Says Games Should Give People the Energy to Keep Going

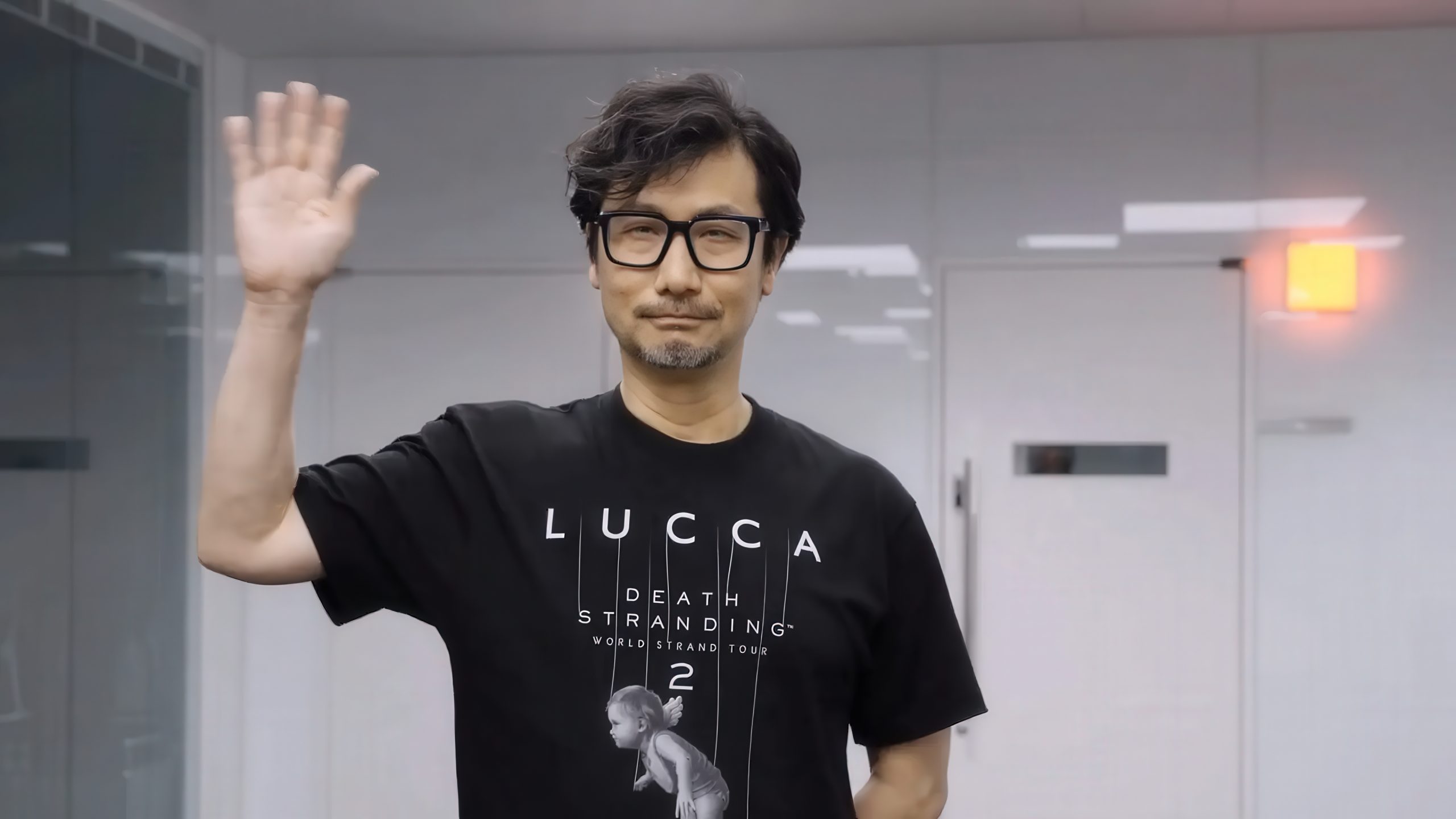

At Lucca Comics 2025, Hideo Kojima took the stage alongside two performers from Death Stranding 2: On the Beach – Luca Marinelli, who portrays Neil Vana, and Alissa Jung, who brings Lucy to life. The conversation ranged from remote performance capture during the pandemic to the day-to-day craft of building a world that players can disappear into for hundreds of hours. Yet one idea rose above production anecdotes: Kojima makes games to help people find the strength to live on and, ideally, to feel a little happier when they put the controller down.

Kojima reflected on his own childhood, describing stretches of loneliness and confusion that many kids feel when the world feels too big and adults don’t seem to have the answers. In that gap, films and books became his lifeline. Characters who struggled, dialogues that lingered, themes that refused to let go – these, he said, gave him energy. They didn’t fix everything, but they offered a compass. Making games, for him, is a way to return that gift.

This outlook is not a marketing slogan. It’s a design principle that shapes how a Kojima Productions title is assembled – moment to moment, system to system. If he asks players to commit dozens or even hundreds of hours, the experience should do more than entertain. Stress relief is welcome, escapism is valid, but the north star is to leave players with something useful: a feeling, a fragment of dialogue, a relationship that reframes how they see their own lives. In Death Stranding 2, the relationship threads embodied by Marinelli and Jung are written to be felt as much as understood, the kind that quietly echo during a commute or a late-night walk.

That’s why Kojima speaks often about immersion. The point of the immersion isn’t only aesthetic fidelity or sprawling maps – it’s empathy. Mechanics, cinematics, and soundscapes are tuned to keep players present with the characters’ inner weather. When he says he hasn’t yet reached his ideal, it’s not false modesty; it’s an admission that this alchemy – turning interaction into meaning – is always unfinished. Each project is a new attempt to bottle lightning: to craft a journey that reminds someone, months or even years later, that they want to keep going.

For long-time followers of Kojima’s career, this philosophy will sound familiar. His games have sparked intense debate precisely because they try to marry pulp spectacle with meditations on connection, responsibility, and the weight of choosing to care. Death Stranding 2: On the Beach, which launched on June 26 for PlayStation 5, met the moment with widespread critical acclaim, with reviewers praising its audacity and its insistence that cooperation and care can be as gripping as conflict.

There’s also a practical footnote that matters for players beyond PlayStation. With the franchise rights now back at Kojima Productions, a PC version – and very likely an Xbox Series S|X release – are expected in 2026, much like the original game’s path to new platforms. That trajectory isn’t just about technical ports; it’s about enlarging the circle of people who might find something sustaining in the journey.

Perhaps that is the quiet ambition behind the spectacle: to prove that a game can be a bridge. Not a cure-all, not a sermon, but a bridge between a hard day and a clearer morning. When Kojima talks about giving players the energy to live on, he’s pointing to a simple but radical test of value. If even one person, years later, can say, “That game helped me when I needed it,” the work has done more than entertain – it has mattered.

And so the experiments continue. New tools will arrive, new collaborators will join, and new constraints – like those pandemic-era remote shoots – will force unexpected solutions. Through it all, the goal remains stubbornly human: build worlds that send players back to their own with a little more courage, a little more connection, and, yes, a little more happiness.