Ghost of Yōtei has quickly become the most talked-about PlayStation exclusive of 2025 – an epic successor to Ghost of Tsushima that not only honors its predecessor’s spirit but expands on it in scale, tone, and emotional complexity. While Death Stranding 2 made waves among the niche art-house gaming audience, Ghost of Yōtei dominates the mainstream, echoing the kind of broad cultural impact few modern games achieve.

Even in its early days, the latest release from Sucker Punch Productions is tracking sales comparable to the PS4-era phenomenon, despite a smaller install base and no pandemic-fueled surge of at-home players.

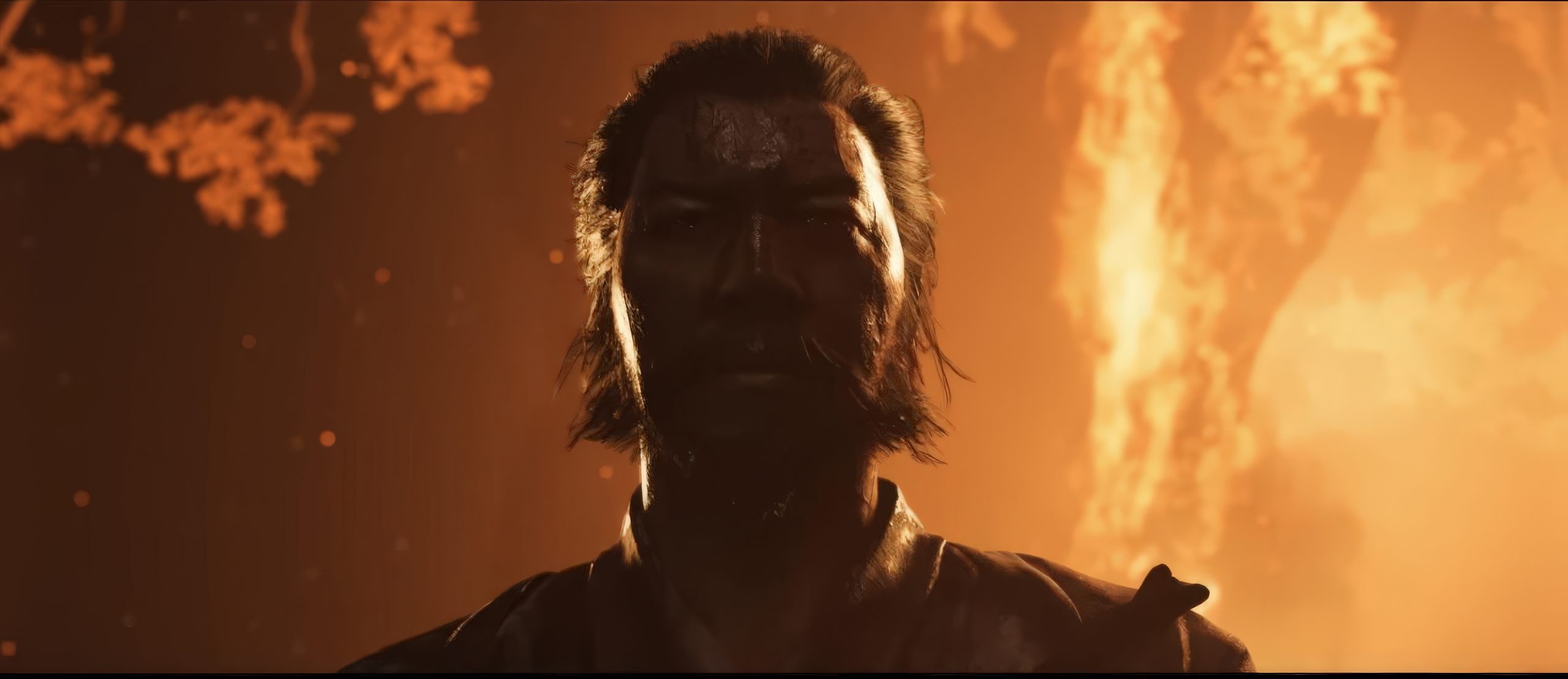

At the heart of this new saga stands Lord Saito, the stoic yet volatile warlord brought to life by veteran actor Feodor Chin. Known for his distinctive voice and motion-capture work, Chin has lent his talents to dozens of projects across gaming, television, and animation – from World of Warcraft to Love, Death & Robots and even Marvel Zombies. His portrayal of Saito in Ghost of Yōtei delivers a nuanced blend of gravitas, cruelty, and tragic conviction, elevating the character far beyond the standard video game villain archetype.

The Challenge of Performing for Games vs. Film

When asked about the difference between acting for games and traditional media, Chin explains that while the core approach to embodying a character remains consistent, the player’s participation changes everything. “In film or TV,” he says, “the audience is passive – they’re observers. But in games, players are participants. That changes how you perform. You still aim for truth, but your energy has to reach the player directly. Sometimes you even command them, and that demands a slightly heightened intensity.”

That insight underscores how acting in games isn’t simply about reading lines. It’s about understanding interaction. A villain like Lord Saito doesn’t just monologue – he taunts, directs, challenges, and pushes the player to act. This interplay between the character’s performance and the player’s decisions creates an emotional tension that’s uniquely interactive. “You want the player to feel something – anger, fear, respect – but it has to feel earned,” Chin adds. “It’s a different kind of dialogue between performer and audience.”

Gaming as an Actor (and a Casual Gamer)

Feodor Chin laughs when asked if he’s a gamer himself. “I enjoy games,” he admits, “but I’m not great at them. My hand-eye coordination is… let’s say, not legendary.” He prefers to play on easy mode, savoring the atmosphere rather than chasing frustration. “It’s supposed to be fun, right? Why turn your leisure into punishment?” he jokes. Still, he proudly recalls getting lost in Ghost of Tsushima for hours when it launched during the early pandemic days – calling it the perfect game for that strange global pause.

“I made my wife a Tsushima widow for a month,” he laughs. “I played nonstop until I finished it. And when I got to the end, I didn’t want to fight Khotun Khan because I didn’t want the game to end. That’s how much I loved it.”

From Lord Adachi to Lord Saito

Chin’s previous appearance in Ghost of Tsushima as Lord Adachi was brief but memorable. Adachi was revered as the greatest swordsman in Japan, only to be betrayed and killed early in the story – a stark symbol of the chaos gripping Tsushima. In Ghost of Yōtei, his role as Lord Saito offered a chance to explore the opposite side of the moral spectrum.

“Adachi was noble and doomed,” Chin reflects. “Saito is driven and brutal – but in his mind, he’s just as righteous. That’s the key to playing villains. You never judge them. A true villain doesn’t see himself as evil. He believes he’s justified.”

That conviction defines Saito’s complexity. He isn’t a caricature of tyranny; he’s a man twisted by loyalty and loss. His rivalry with the protagonist, Atsu, mirrors a philosophical conflict – vengeance versus forgiveness. “They’re two sides of the same coin,” Chin says thoughtfully. “Both act out of loss. Both crave justice. But Atsu learns to let go, while Saito can’t.”

In the climactic duel, Saito’s haunting line – “We are the same” – lands with a weight that transcends words. “That’s the tragedy,” Chin notes. “He’s right, but he can’t change. Atsu breaks the cycle; Saito becomes the cycle.”

Behind the Scenes: Motion Capture and Cinematics

Unlike many pandemic-era productions, Ghost of Yōtei was made largely in-studio, with extensive motion-capture sessions at Sony’s Santa Monica facilities. “It’s a full-body experience,” Chin says. “You wear the suit, the facial cameras, the sensors – it’s like theater mixed with sci-fi. You’re acting in an empty room, imagining castles and battlefields, and somehow it all becomes real.”

Chin admits the process can be physically demanding but also liberating. “It takes you out of your comfort zone. You’re performing for an invisible world that’ll be filled in later. But when you see the final product – the lighting, the animation, the music – it’s like magic. It’s incredibly rewarding.”

Unlike film, where the set and costumes guide you, mocap acting demands imagination and trust in the team. “You have to picture everything,” he explains. “That’s where collaboration with the directors and animators becomes essential. They help you see the invisible world you’re in.”

The Rise of Cinematic Games

Chin sees modern video games as an artistic evolution of cinema itself. “They’re the new movies,” he says. “Games today have the same scope, budgets, and emotional storytelling as major films – sometimes more. And players don’t just watch; they feel what the character feels. That’s why I love this medium.”

After Ghost of Yōtei, Chin hopes to continue working in gaming, particularly in performance capture roles. “It challenges you as an actor,” he says. “You have to use your whole body, your imagination. It’s pure acting stripped of vanity – no costumes, no makeup, just raw performance.”

On AI and the Future of Performance

When the conversation turns to artificial intelligence in the entertainment industry, Chin grows reflective. “Like any technology, AI can be a useful tool. But it should never replace people,” he says firmly. “The soul of performance comes from human experience – our imperfections, emotions, instincts. You can’t replicate that.”

He acknowledges that AI-generated voices and animations are advancing rapidly, but insists that the emotional nuance – the humanity – is irreplaceable. “Audiences connect to people,” he says. “They react to the vulnerability, the unpredictability that only humans bring. That’s what makes storytelling alive. AI might mimic it, but it can’t feel it.”

Legacy of Ghost of Yōtei

As we wrap up, Chin expresses gratitude for being part of something special. “It’s surreal,” he says. “When I see players sharing clips, quoting Saito, creating fan art – it reminds me that games like this connect people across the world. That’s powerful.”

He pauses, smiling. “I’ll admit, though, it’s weird to be the villain everyone hates. My mom saw gameplay on YouTube and said, ‘Why are you so mean?’”

Ghost of Yōtei continues to dominate discussions not just for its visuals or combat, but for its thematic resonance. It’s a story about rage and redemption, vengeance and mercy – all framed through characters that feel painfully human. And in that sense, Feodor Chin’s Lord Saito might just be one of the most memorable villains of this console generation – not because he’s evil, but because he’s understandable.

As Chin puts it: “The best villains are mirrors. You see a part of yourself in them – the part you wish wasn’t there.”

Ghost of Yōtei doesn’t just continue the legacy of Tsushima – it expands it. And thanks to performers like Feodor Chin, it reminds us why video games, at their best, aren’t just entertainment. They’re empathy machines.