The global memory industry is in the middle of a once-in-a-generation demand surge, yet the two companies that dominate DRAM output, Samsung and SK hynix, are in no rush to open the taps. Together they control well over two-thirds of the market, and instead of racing to flood the world with cheap RAM, both are openly saying that the priority in this so-called memory supercycle is long-term profitability, not short-term relief for prices.

For consumers, that decision is already biting.

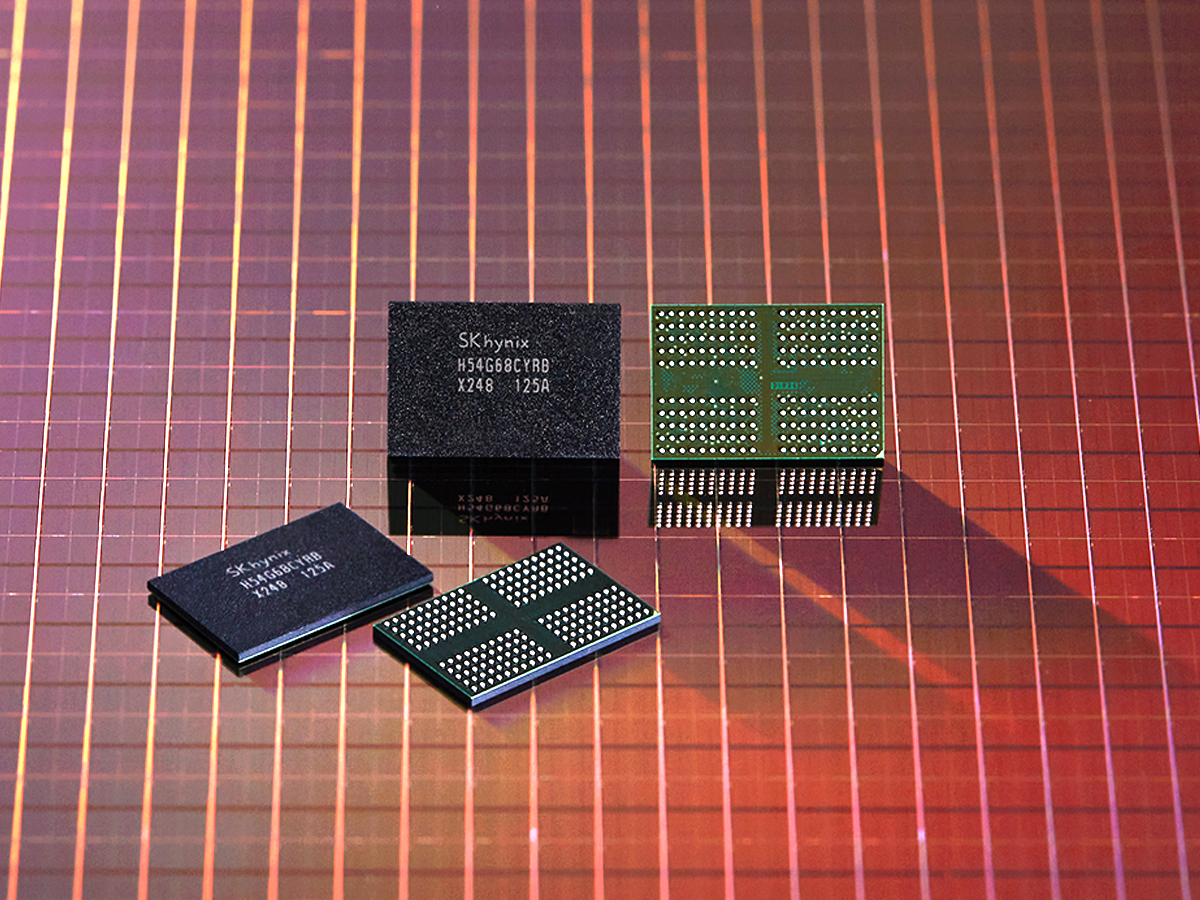

Desktop RAM kits, laptop upgrades and even the memory chips soldered onto graphics cards and game consoles have climbed sharply in price over the past few months. What used to be an easy, relatively cheap way to speed up an ageing PC now feels like a luxury purchase. Behind that sticker shock sits a deliberate strategy: maintain tight supply, sign shorter contracts and let prices reset higher as AI, data-center and high-bandwidth memory (HBM) orders soak up every available wafer.

From pandemic crash to AI gold rush

To understand why chipmakers are so cautious, you have to rewind a few years. During the COVID era the DRAM business went through a brutal downturn. PC and smartphone sales stalled, cloud customers paused orders, and manufacturers were sitting on warehouses full of unsold chips. To survive, Samsung, SK hynix and their rivals slashed output and cancelled or delayed capital-intensive fab projects. That deep production cut is still baked into today’s capacity.

Now the pendulum has swung the other way. Generative AI, recommendation engines and large-scale cloud services guzzle memory in quantities the PC market never did. Nvidia’s AI accelerators, for example, ship with gigantic stacks of cutting-edge HBM, each one built on the same DRAM manufacturing lines that could otherwise feed consumer DDR5 modules. When data centers are willing to pay almost any price to secure supply, it is easy to see why memory makers prefer to keep production tight.

A strategy built around CAPEX and scarcity

Samsung has been unusually blunt about this approach, saying that instead of rapidly expanding facilities it will pursue a capital expenditure strategy designed to balance customer demand and pricing, explicitly to avoid oversupply. In practice that means stretching out investments in new lines, keeping utilisation high on existing tools and signing short-term supply agreements where price hikes can be passed on more quickly. SK hynix is following a similar path.

Critics see something more cynical at work. To them, this looks like a textbook case of engineered scarcity: throttle output, blame the AI boom and enjoy record-high margins while everyone else scrambles. The DRAM industry has, after all, been fined in the past for price-fixing and cartel-like behaviour. That history makes it easy for frustrated PC builders to call today’s alignment on discipline a cartel in everything but name.

Regulators, rivals and the China wildcard

Regulators are already under pressure to pay attention. Commenters argue that if memory is a strategic resource for AI and national infrastructure, governments should not simply shrug when a tiny club of suppliers lets prices spike. Some even float the idea that companies should be obligated to raise production in the public interest when shortages become extreme.

At the same time, others argue that the real fix will come from competition. Chinese DRAM makers, heavily backed by state funding, are racing to ramp up conventional DRAM and even high-bandwidth products. The challenge is yield: it is one thing to pour a gorillion wafers into fabs, another to get cutting-edge HBM2E or HBM3 chips out in commercially viable volumes. Export controls, sanctions and tooling restrictions slow that race further, which conveniently buys the established giants more time to enjoy the current supercycle.

New fabs in the US, Europe and elsewhere are also on the horizon, but these projects run on multi-year timelines. By the time many of them are fully online, around the middle to late part of this decade, the current wave of AI demand may either have normalised into steady structural growth or deflated if the most aggressive predictions about near term AGI fail to materialise.

Bubble or the new normal?

That is the other big question hanging over the market: is this memory squeeze a temporary bubble, or the start of a fundamentally different era? Some investors insist the AI rally is overhyped and that we are replaying the GPU shortages of the crypto boom, with Nvidia’s CEO Jensen Huang cast as the high-tech gold-rush baron who wants all the RAM in the world for the next few years. Others argue that even if today’s hype cools, workloads like AI inference, 3D worlds, scientific computing and cloud gaming will keep DRAM demand elevated far above the pre-2020 baseline.

Samsung and SK hynix are clearly betting that, bubble or not, they are better off stair-stepping capacity and defending prices than building fabs as if demand will grow in a straight line forever. They would rather risk a few years of grumbling about expensive RAM than repeat the brutal price crash that follows every overbuilding cycle.

What this means if you need RAM

For ordinary buyers the message is sobering. Industry projections already talk about tight supply stretching into 2028, and both big players are locking in contracts that let them adjust prices rapidly as the market moves. In plain terms, that suggests that everything from basic DDR5 kits to high-end GPUs and consoles will stay under pressure for several more quarters, with only brief dips when demand pauses.

Some enthusiasts are choosing to wait, leaving greedy vendors to stare at stock that is not moving. Others compromise by buying slower, cheaper modules, value-oriented DDR5 with loose timings, just to get new systems built. A few even find humour in the situation, joking about non-binary 24 GB sticks and treating them like a meme rather than a serious upgrade path.

In the end, the balance of power is not entirely one-sided. If buyers delay upgrades, regulators keep a close eye on coordination, Chinese and other challengers improve yields and the newest fabs ramp on schedule, the grip of the current duopoly could loosen. Until then, though, Samsung and SK hynix look determined to ride this supercycle for all it is worth, and anyone pricing a new PC today and over the next few years is paying the bill.

1 comment

So they basically learned the GPU playbook from Huang, starve the market, blame the boom, cash the checks, nice