Chopard L.U.C Grand Strike: When A Grande Sonnerie Becomes A Living Machine On The Wrist

Every once in a long while, high watchmaking delivers something that feels less like a new reference and more like a decisive full stop at the end of a chapter. The Chopard L.U.C Grand Strike belongs in that rare category. It is not just another limited run, highly complicated dress watch; it is a fully fledged acoustic machine designed to live on the wrist, shout the time into the room, and quietly rewrite a lot of assumptions about what a chiming watch can and should be

. With its grande sonnerie, petite sonnerie and minute repeater functions, sapphire crystal gongs, obsessive power management and a movement submitted to chronometer testing while actually chiming, this watch reads like the answer to a challenge nobody else really wanted to confront.

For years, collectors accepted chiming watches as fragile, temperamental little miracles that whispered their song only when the room fell silent and everyone leaned in. The sound was often thin, the cases felt delicate, and real performance was rarely the focus. The L.U.C Grand Strike arrives from a very different mindset. It is the follow up to Chopard’s own Full Strike, the minute repeater that already shook up expectations with sapphire gongs bonded to the front crystal. Now, with a full grande sonnerie architecture built on top of that platform and roughly eleven thousand hours of research and development behind it, the Grand Strike tries to answer a brutally simple question: what would happen if a manufacture decided to push every aspect of sonnerie watchmaking to the limit, not only on paper, but in daily, repeatable use.

Of course, this is also a watch that ignites strong opinions the second you see it. The case is precious and very expensive; the dial is open, dense and controversial.

Some will call it unreadable and wish all that mechanical fireworks had been left for the caseback. Others will look at the same face, hear that powerful chime and shrug that time legibility is almost secondary here. Beyond the aesthetics, though, lies a genuinely fascinating lesson in micro engineering, acoustics, chronometry and reliability testing, and that is where the L.U.C Grand Strike becomes truly compelling.

Chiming Watches 101: From Simple Strikers To The Sonnerie Summit

To understand what Chopard has built, it helps to climb the chiming watch hierarchy step by step. At the base you find the hour striker. This type of watch simply marks the passing of each hour with a single chime, usually on a gong wrapped around the movement and struck by a tiny steel hammer. It is an automated reminder that time has moved on, like a very polite little bell in the background. Modern examples range from relatively accessible pieces from smaller brands to elaborate executions from established manufactures, but at heart they all perform a straightforward task: on the hour, they ring once, and then they go back to sleep until the next full hour arrives.

From there, we move into the realm of repeaters, with the minute repeater being the best known. Unlike an hour striker, a minute repeater does not constantly watch the clock and trigger itself. Instead, it waits for the wearer to request the time. When the appropriate slide or pusher is activated, the mechanism performs a carefully choreographed sequence of chimes, first counting out the hours, then the quarters past the hour, and finally the minutes since the last quarter. Low notes, combined tones and high notes are used in varying sequences to encode the current time purely in sound. It is a wonderfully theatrical complication: the watch remains visually unchanged, but a hidden acoustic drama unfolds whenever you ask it to speak.

Sitting above both is the rarefied territory of sonnerie watches. Grande and petite sonnerie pieces bring together the two ideas just described: they have the ability to chime the passing of time automatically, and they can also act as repeaters on demand. In a grande sonnerie mode, the watch strikes the full hours and then announces every quarter with both the hours and the quarters. A petite sonnerie, by contrast, strikes the hours on the hour but only the quarters at the quarter marks

. In both cases, when the wearer activates the repeater, the watch can still recite the current time like a conventional minute repeater. Designing a sonnerie means you are engineering a small mechanical orchestra that plays according to a calendar of triggers, but can also be thrown into a solo performance at any moment.

This dual nature is why the sonnerie is often described as the summit of chiming watchmaking. A simple striker performs one automatic gesture. A minute repeater responds powerfully on command but is silent otherwise. A sonnerie must master both behaviours without ever tripping over itself. Doing that in a movement that has to fit under a normal cuff is a monumental mechanical challenge, and doing it with good sound, robust safety systems and reliable chronometric performance pushes the whole exercise into extreme territory.

Why Building A Grande Sonnerie Is So Difficult

On paper, the hardest part of a sonnerie might seem like the packaging problem: how to fit the additional racks, levers, governors, gears and springs into a movement that still has to drive the hands, manage the calendar of chimes and absorb the shocks of daily wear. There certainly is an element of mechanical Tetris going on; the L.U.C Grand Strike movement contains hundreds of parts that have to coexist within a footprint compatible with a 43 millimetre case. But size alone is not the true killer. The most serious difficulties are more subtle and interlinked.

First there is power. Every chime consumes energy, not just when the hammers strike but also in the long build up as springs are wound and cams are armed in preparation for the next activation. Think of the chiming system as a secondary machine that is constantly charging itself from the main barrel while the timekeeping train also asks for a perfectly stable flow of torque. Whenever the sonnerie is getting ready to ring, it is effectively tapping into the same energy reservoir that has to keep the balance wheel oscillating within chronometer tolerances. If the chiming system is thirsty or badly regulated, it will drag on the timekeeping as it charges, and accuracy will suffer.

Then comes safety. A sonnerie is a complicated mechanical stack with dozens of parts moving in overlapping sequences during each chime. In the hands of a distracted owner, it is also a device that practically invites abuse: someone tries to set the time while the chime is in progress, presses the crown pusher at a bad moment, or toggles the strike mode back and forth while the racks are already engaged. Without sophisticated blocking systems and fail safes, such interventions can cause levers to collide, teeth to shear and springs to unleash their stored energy in all the wrong directions. The result is the horological equivalent of a computer crash, except the restart involves a trip back to the manufacture and a repair bill that rivals a luxury car.

Finally, there is the matter of sound. For decades, connoisseurs were willing to forgive chiming watches for sounding plain, thin or just barely audible. Cases were often designed more for visual elegance than for acoustic projection, and many manufactures did not seriously measure or optimise the sound they produced. The magic of seeing a repeater mechanism in motion, and the sheer improbability that it worked at all, seemed enough to justify the huge prices asked for those pieces. In that older context, the idea of a chiming watch that is not only mechanically clever but also loud, warm and clearly musical was still more the exception than the rule.

From Strike One To Full Strike: How Chopard Changed The Rules

Chopard has been interested in chiming watches for a long time, but the L.U.C Grand Strike does not appear from nowhere. Before it, there were the Strike One models, which experimented with an hour striker complication within the L.U.C family. Those watches already showed that the brand was willing to invest in acoustic complications, but the real turning point came with the introduction of the L.U.C Full Strike in 2016. That watch took a radically different approach to the problem of how to make a repeater truly audible on the wrist without relying on gimmicks like external amplifying boxes.

The crucial idea in the Full Strike was to integrate the gongs into the sapphire crystal that covers the dial. Rather than attaching round steel gongs to the movement and relying on the case to act as a resonant chamber, Chopard engineered gongs that form a single piece with the crystal itself. The gongs have a square cross section to increase the contact area with the hammers, and when those hammers strike, the vibrations travel directly into the broad surface of the crystal. Suddenly the entire front of the watch behaves like a loudspeaker cone, projecting sound outward with far more efficiency than a conventional set up. This, combined with careful regulation of the striking speed via a silent governor, gave the Full Strike a voice that felt dramatically louder and more pleasant than what many collectors were used to.

From the outside, the Full Strike looked like a bold but self contained project: a minute repeater that finally sounded as impressive as it was mechanically complex. Inside the manufacture, however, it was also a platform and a proof of concept. The sapphire gongs, the crystal acting as a resonator, the way the movement interacted with that acoustic structure and the solutions developed for power distribution and safety all formed the foundation for something more ambitious. When Chopard later decided to build a true grande sonnerie on that base, every aspect had to be rethought and pushed further, but the basic conviction remained the same: a chiming watch should not whisper. It should sing.

The Acoustic Engine: Sapphire Crystal Gongs Turned Up To Eleven

The L.U.C Grand Strike continues and refines that same acoustic philosophy. The watch uses a monobloc sapphire crystal that does more than simply cover the dial; it extends down and around, wrapping part of the movement in a rigid, transparent shell. The gongs are not separate metallic rings but sculpted parts of this single sapphire element. When the two steel hammers mounted on the movement strike them, the vibrations flow uninterrupted through the crystal structure and into the broad frontal surface that faces the wearer and the surrounding air.

This design does two important things at once. First, it maximises the efficiency of energy transfer from the hammer to the vibrating surface. Very little of the impact is lost in joints or soft interfaces because the gong and crystal share the same material. Second, it gives that vibration a huge radiating area compared with traditional gongs. Instead of a slender wire trying to push sound waves into the case and through a relatively small dial opening, the entire crystal transforms into a kind of mechanical loudspeaker membrane. The result is a chime that is not only louder but also fuller, with a perception of body and warmth rather than the dry, metallic tinkle that many collectors grudgingly accepted from older repeaters.

Chopard did not simply rely on subjective impressions to evaluate this sound. The brand worked with the engineering school Haute Ecole du Paysage, d’Ingénierie et d’Architecture in Geneva, using an anechoic environment to measure the acoustic performance of the Grand Strike and to compare it with traditional steel gong systems. Loudness, decay, clarity and the distribution of frequencies were all analysed. Interestingly, the move to slimmer hammers in the Grand Strike, partly motivated by the need to balance power consumption and consistency, ended up improving the sound further. Measurements showed a slight gain in loudness compared with earlier sapphire gong prototypes and a warmer tonal balance with a reduction of harsh overtones.

In person, the impression is that of a chime that feels surprisingly present even when you are not consciously focusing on it. You do not have to cup the watch in your hands or lean in close to catch the sequence of hours, quarters and minutes; the sound floats out into the room with easy confidence. At the same time, there is a softness to the attack that keeps it from feeling shrill. The tones bloom and overlap in a way that feels musical rather than clinical, and that might be the most convincing argument for the sapphire concept: it is not only a trick to get more decibels, but a serious attempt to craft a specific acoustic signature.

The L.U.C 08.03-L Movement: Micro Mechanical Choreography At High Speed

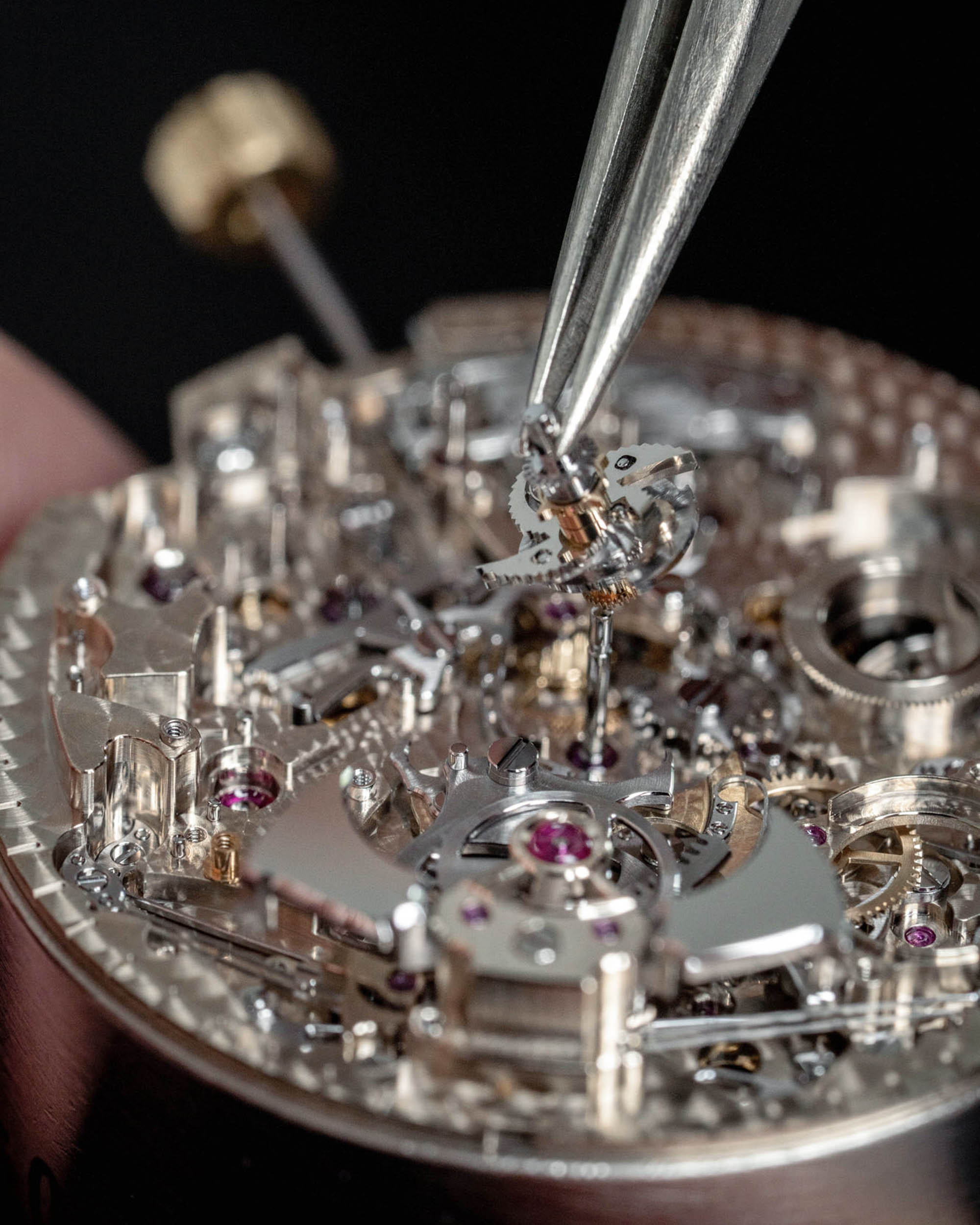

Beneath that resonant sapphire shell, the L.U.C Grand Strike is powered by the calibre L.U.C 08.03-L, a hand wound movement consisting of hundreds of carefully finished components. Chopard speaks of 686 individual parts inside this architecture, each of them decorated by hand and individually inspected to meet the requirements of the Geneva Seal. That alone is a formidable undertaking; finishing bridges, levers, springs and wheels to that level in such quantities is labour intensive by any standard. But the Grand Strike is not simply about static beauty under a loupe. It is also about motion, timing and microscopic tolerances.

One of the most striking aspects of the mechanism is how quickly the chiming train transitions from rest to full engagement. Chopard describes a cluster of roughly thirty four components that move from standby into position within roughly three hundredths of a second whenever the sonnerie or repeater is triggered. These elements are guided and restrained by an array of finely tuned blade springs, creating a kind of mechanical ballet in miniature. For the wearer, that choreography is invisible; all they perceive is the confident start of the chime. For the watchmaker, adjusting the sequence so that every lever, rack and cam arrives exactly when and where it should, without collision or hesitation, is one of the hardest practical challenges of the whole project.

This is also the reason why each Grand Strike is assembled and regulated by a single master watchmaker rather than being passed from station to station. Even with extremely tight industrial tolerances, small variations in how different parts interact will demand unique fine tuning for each movement. One piece may reach stable operation after a matter of days, another might require weeks of incremental adjustment, with repeated cycles of disassembly, microscopic tweaking of shapes, refinishing of modified surfaces and reassembly. Handing such a work in progress to a new person halfway through would mean losing the mental map of what has already been tried, what worked and what did not. Assigning the entire birth of a movement to one watchmaker is therefore less a poetic gesture than a practical necessity.

Finishing, Certification And The Rare Tourbillon That Has To Prove Itself

Visually, the movement is decorated to a level that earns both the Geneva Seal and, perhaps more unusually for such a complex piece, a chronometer certificate. Anglage, perlage, black polishing and careful straight graining are found throughout. What makes this watch stand apart is that Chopard did not stop at aesthetic finishing. The brand also decided to submit the Grand Strike to the COSC chronometer testing body. On its own this would already be a vote of confidence. Doing it while the watch operates as a petite sonnerie is something else entirely.

Most tourbillon watches are never submitted to external performance testing, and the ones that are do not usually have to contend with a chiming mechanism that periodically drains power from the same barrel feeding the escapement. In many corners of the market, the tourbillon has become a kind of visual talking point, a complication sold on the promise of superior accuracy without being asked to actually prove anything. Chopard went in the other direction. The Grand Strike’s tourbillon is not there to spin gracefully under a bridge while everyone politely assumes it must be precise; it is asked to deliver the stable timing necessary to satisfy COSC standards while the sonnerie cycles through its modes in the background.

There is a certain stubbornness in that decision. Submitting such a movement to COSC means accepting that if the interaction between the chiming train and the going train is not perfectly managed, the timing results will show it. It also forces the engineers to quantify and control something that many brands are happy to leave as an untested abstraction: how much does the energy drawn to charge the sonnerie in the minutes leading up to each strike actually disturb the amplitude of the balance. The fact that the Grand Strike can meet the chronometer criteria in this context suggests that all the work poured into power management is not just theoretical.

Power Management: Two Barrels, One Hungry Sonnerie

Inside the Grand Strike, Chopard separates responsibilities between two mainsprings. One barrel is dedicated to timekeeping, the other to the chiming mechanism. That sounds clean and simple, but the actual flows of energy are more intertwined than a superficial description might suggest. The barrel for the chime has to be rewound periodically so that the hammers can perform their sequences at full strength, and the act of charging that barrel is ultimately powered by the wearer when they wind the crown, which simultaneously reserves a portion of torque for the timekeeping side.

More interestingly, the way energy is prepared for a strike is not a sudden gulp taken at the moment of chiming. Instead, the sonnerie gradually charges itself in the background, using small doses of energy to arm springs and position components over the course of the fifteen minutes between quarter marks. By the time the watch reaches a point where it has to ring, a lot of the necessary work has already been done. That strategy has two goals. It avoids a large instantaneous drain that might badly disturb the balance, and it allows the movement to spread the energetic cost of the sonnerie more evenly across time. Nevertheless, the fact remains that the more often the chiming system demands preparation, the more carefully the timekeeping train has to be protected.

Here lies the somewhat counterintuitive detail: the petite sonnerie mode, which might at first seem the gentler option, actually imposes a higher energy threshold than the grande sonnerie. By omitting hour strikes at the quarter marks, the petite sonnerie requires a more complex braking and suppression system. That system itself consumes energy and applies additional load to the chiming train, effectively shortening the usable power reserve for the strike. It is the kind of nuance that only appears when you really dig into the mechanics, and it further illustrates why Chopard’s decision to seek chronometer certification while the watch runs in petite sonnerie mode was not merely a flourish, but a genuine technical challenge.

Patents, Protection And The Art Of Not Blowing Up A Sonnerie

Given how delicate the interactions inside a sonnerie can be, building robust safety measures is not optional. Chopard’s engineers dug through both their own history and old technical literature, borrowing and reinterpreting ideas from calendar mechanisms, previous striking watches and even expired patents originally meant for ballpoint pen buttons. In total, the Grand Strike incorporates around ten proprietary technical solutions dedicated to its strike work alone, half of them created specifically for this project.

Some of these patents focus on the sequence and cadence of the chimes, ensuring that the watch never miscounts or overlaps elements in a way that would muddle the time announced. Others concentrate on mechanical interlocks and clutches that prevent the activation of certain functions when the movement is in a risky state. The slider that selects between grande sonnerie, petite sonnerie and silence is designed to work in concert with the crown pusher for the repeater and the setting functions, reducing the chance that an enthusiastic owner can accidentally force gears and levers to fight each other.

It is easy to gloss over such things when reading technical descriptions, but in practice these protections are the difference between a watch that feels intimidating to use and one that invites interaction. A grande sonnerie that constantly makes you worry about breaking it is a sculpture on the wrist. A grande sonnerie that can survive clumsy fingers, occasional impatience and years of repeated activations without complaint is much closer to a true machine for daily enjoyment. The Grand Strike aims firmly for the latter category, and the amount of energy Chopard poured into patents and safeguards makes that ambition credible.

Reliability Torture Tests: Half A Million Chimes Before A Customer Ever Hears One

All of this engineering would remain theoretical if it were not backed up by serious testing. Here again, Chopard pushes the project into slightly obsessive territory. Before a Grand Strike is deemed ready to leave the manufacture, its sonnerie mechanism is subjected to a cycle of tens of thousands of activations designed to simulate years of enthusiastic real world use. The watch spends months on a bench, under a glass dome or inside specialised rigs, constantly chiming while instruments monitor its behaviour.

The sonnerie is triggered in both grande and petite modes over an accelerated schedule, reaching well over sixty thousand automatic activations that, taken together, correspond to roughly five years of steady wearing. In parallel, the minute repeater function is repeatedly launched via the pusher in the crown thousands of times to make sure that even heavy use of on demand chimes does not create unusual wear or failures. By the end of this campaign, the sapphire crystal gongs will have been struck more than half a million times. Only then does Chopard consider the acoustic system and the underlying mechanics to have proven themselves durable enough for customer delivery.

There is something quietly charming about the mental image of such a watch chiming away night and day in a workshop, marking quarters and hours for nobody in particular, like a miniature tower clock under a bell jar. It also underscores how far the brand has travelled from the old mindset where the main goal was simply to make the mechanism work at all. Here, repeatability and resilience are just as important as visual finissage, and that emphasis suits a watch that positions itself as a full spectrum celebration of mechanical craft rather than a fragile showpiece.

Case, Dial And Presence: A Basin Of Ethical Gold Around An Industrial Sculpture

All that engineering might have been packaged in a discreet, closed dial design, but Chopard clearly decided that the movement deserved to be seen and discussed. The L.U.C Grand Strike comes in a forty three millimetre case crafted from the brand’s so called ethical white gold, a metal sourced according to strict internal traceability standards. The profile of the case is interesting: a pronounced concave bezel, which dips inward rather than swelling outward, sits above a middle case that narrows towards the back, giving the watch a basin like silhouette. On the wrist, this shape helps the watch feel less monolithic than its diameter might suggest. The concave bezel captures shadows instead of reflections, visually slimming the front view and framing the exposed mechanics.

Turn your attention to the dial side and there is no avoiding the fact that Chopard wanted to foreground the machine more than traditional notions of elegance. Bridges, racks, cams, hammers and the tourbillon cage are all on display. A chapter ring and hands float above this landscape, and there are islands of more familiar watchmaking language in the form of power reserve indicators and refined finishing, but the overall impression is one of controlled complexity. It is, deliberately, not a quiet watch. Some enthusiasts will be delighted; for them, every glance at the wrist becomes an opportunity to trace the pathways of force through the mechanism and to appreciate the layers of handwork. Others will find the scene overwhelming, even chaotic, and wish that Chopard had hidden most of this engineering on the reverse, leaving a clean enamel or textured dial for daily use.

The question of legibility is therefore not academic. Depending on lighting, eyesight and taste, the Grand Strike can range from surprisingly readable to nearly impossible to parse at a casual glance. In photographs, the skeletonised hands and the wealth of background detail can make the time hard to pick out. In person, the depth of the dial and the contrast provided by the hands go some way towards helping, but this will never be a piece you buy because you want instant clarity. That is a conscious trade off. Chopard has built a chiming instrument that invites you to hear as much as to see, and the visual language reflects that priority. Whether you consider that a flaw or a fair price for such mechanical theatre will depend entirely on your personal balance between utility and fascination.

The use of ethical white gold as the case material adds another layer to the conversation. On a technical level, gold’s relatively low stiffness and high density can contribute positively to the way a chiming watch sounds, and Chopard has clearly tuned the case to work in concert with the sapphire crystal. On a symbolic level, the ethical sourcing message will resonate with some buyers and leave others indifferent or even mildly cynical, especially given the price point. In any case, the metal has a subtly warm hue that prevents the watch from looking too cold or clinical. It softens the industrial impression of the open dial and brings the piece back into the realm of high jewellery, at least visually.

A Sonnerie Versus A Perpetual Calendar: Different Kinds Of Intelligence

When collectors talk about top tier complications, perpetual calendars often share the stage with chiming watches. Both demonstrate a kind of mechanical intelligence, a capacity to track abstract information and express it in a surprisingly human way. A perpetual calendar quietly calculates the alternating lengths of months and the rhythm of leap years, advancing its indications so that the date remains correct for decades without intervention. A sonnerie observes the passing of time and comments on it aloud, transforming abstract numerals into a melody of intervals.

In daily life, however, the difference in how often these mechanisms actually do something perceptible is striking. A perpetual calendar reveals its cleverness only a handful of times per year, whenever the date jumps from a shorter month to a longer one or handles a leap day without human correction. The rest of the time, it advances its hands and discs just like any other watch. A grande sonnerie, by contrast, offers a small performance every quarter hour, day in and day out. Every fifteen minutes, it asks for a little attention with its chime, a reminder that inside that polished case there is a complex machine thinking about time in concentric cycles of hours and quarters.

That is why some enthusiasts feel that a well executed sonnerie offers a more constant sense of presence than many other complications. With the Grand Strike, this effect is amplified by the sheer quality and volume of the sound. You do not have to schedule special moments to enjoy it; the watch handles that for you, peppering your day with musical time checks. The emotional connection that forms as you begin to anticipate and recognise those patterns can be surprisingly strong, and that is one of the intangible reasons why collectors who fall for this type of watch tend to see it as the end of a long journey rather than just another step.

Design Debates: Beauty, Industrial Aesthetics And Comparisons

None of this technical achievement exempts the Grand Strike from aesthetic scrutiny. The world of high end chiming watches already includes pieces that many consider benchmarks of visual harmony, from certain German manufactures that favour sculptural bridges and clean typography to independent makers who hide their most complex mechanisms behind sober dials. In that context, Chopard’s decision to present the Grand Strike with an open, almost architectural front side invites comparison and, inevitably, criticism.

Some seasoned observers have argued that while the movement is undeniably impressive, it is not conventionally beautiful. They point to the prevalence of plates and straight edges, the density of visible components and the somewhat technical character of the layout as elements that contrast with the romantic image of classical haute horlogerie. For those critics, this is a watch whose most photogenic side should have been reserved for the caseback, leaving space on the front for a more restrained, legible dial. From that standpoint, the current design feels as if the watch has been cased upside down.

Others take almost the opposite view. For them, the open dial is exactly what makes the Grand Strike special. It turns what could have been a private mechanical spectacle into something you can share with anyone who asks about your watch. The interplay of polished and brushed surfaces, the glint of the tourbillon cage, the visible racks that prepare for each chime, all these details contribute to a sense that you are wearing a living instrument rather than a closed jewel. Imperfect legibility is part of the deal, but so is the ability to point at nearly any visible component and tell a story about what it does.

It is worth remembering that this is not a piece meant to court broad consensus. At its price level, it addresses a very narrow audience that is comfortable with bold decisions and willing to accept them as part of the watch’s identity. That does not mean design critiques are invalid; if anything, the Grand Strike is more interesting because it triggers such mixed reactions. But it does suggest that Chopard was aiming for a kind of industrial theatre rather than timeless understatement, and that is exactly what it delivered.

The Cost Of Pushing Boundaries: Price, Scarcity And Context

No discussion of the Grand Strike can ignore its cost. With a price in the region of seven hundred and eighty thousand Swiss francs, this is emphatically not an aspirational piece for most collectors. It sits in the same stratosphere as grande sonnerie works from the most established traditional houses and a number of highly limited creations from niche independents. At that level, price comparisons become somewhat abstract. The bill reflects not only the materials, handwork and finishing but also the years of research and the relatively tiny number of pieces that will ever be made.

From one angle, it is tempting to treat such numbers as a kind of luxury tax on horological obsession, a fee that a handful of clients are willing to pay so that the rest of us can admire the results from afar. From another, more charitable angle, watches like the Grand Strike serve as laboratories whose discoveries eventually trickle down into more accessible lines. Chopard’s work on acoustic propagation, power management and safety mechanisms does not have to remain confined to this single reference. Elements of it can and likely will influence future chiming watches at lower price points, whether under the L.U.C umbrella or in other collections.

Either way, the Grand Strike sends a clear signal about how seriously Chopard takes its role in high watchmaking. It is relatively easy to produce a visually impressive complication and sell it on brand prestige alone. It is much harder to commit to the kind of deep, systemic rethinking of a complication that this watch represents, to back that up with objective performance testing and long term durability trials, and then to put the result into the market knowing full well that most observers will only ever encounter it through photographs and videos.

Why The L.U.C Grand Strike Matters Beyond Its Owners

In the end, the significance of the L.U.C Grand Strike goes beyond the small group of clients who will strap it on. It demonstrates that there is still room for meaningful innovation in fields that some considered mature or even exhausted. Chiming watches have existed for more than a century. The grande sonnerie format is not new. Yet by rethinking how to transmit sound, how to manage energy flows and how to validate performance, Chopard has shifted the expectations for what such a watch can be in the twenty first century.

It also highlights a path that other manufactures may follow if they choose. Rather than treating complications as static traditions to be reproduced with incremental cosmetic changes, they can be approached as living technologies open to improvement. That does not mean abandoning hand finishing or decorative artistry; the Grand Strike shows that it is entirely possible to combine traditional craftsmanship with modern measurement tools and a willingness to question habits. It turns out you can have Geneva Seal level finishing and an insistence on chronometric testing in the same piece, even when the movement is festooned with hammers, gongs and racks.

For enthusiasts watching from the sidelines, the Grand Strike offers a rich case study in what happens when a brand refuses to be satisfied with good enough. All the difficult topics that many prefer to keep vaguely defined in marketing copy, such as real world sound quality, shock resistance, long term reliability and genuine accuracy, are dragged into the light and dealt with head on. Whether you love the open dial, loathe it, or vacillate between both positions, it is hard to deny that the end product feels like the result of a coherent, sustained vision.

Conclusion: A Living, Breathing Statement Piece

Viewed coldly, the Chopard L.U.C Grand Strike is a hand wound tourbillon watch in ethical white gold with a grande sonnerie, petite sonnerie and minute repeater, sapphire crystal gongs, dual barrels, Geneva Seal finishing and COSC certification, priced at a level that guarantees extreme rarity. Viewed more emotionally, it is something a little stranger: a small living machine that punctuates your day with music, demands a certain tolerance for visual complexity and rewards those who are willing to learn how to read and listen to it at the same time.

It is not perfect in the sense of universal appeal. The aesthetics will be divisive, the legibility will annoy some owners, and the marketing language around ethical materials will roll a few eyes. Yet that is part of its charm. This is not a neutral exercise designed by committee. It is a watch that clearly reflects the obsessions of the people who created it, from the watchmakers hunched over individual movements for weeks to the engineers measuring decibels in silent rooms and the designers sketching concave bezels and basin shaped cases.

For those of us who will never own one, the Grand Strike still fulfils an important role. It reminds us that mechanical watchmaking, at its most ambitious, is not content to reprint the past. It is willing to rethink complications from the ground up, to invest unreasonable amounts of time and ingenuity to make something that is both objectively impressive and deeply, delightfully unnecessary. In that sense, the Chopard L.U.C Grand Strike feels like one of those rare creations where you can almost imagine a team stepping back after eleven thousand hours of effort and saying, half joking, that they could stop here and call it a day. Of course they will not. But if you want to know what it looks and sounds like when a manufacture briefly reaches for that kind of final statement, you could do much worse than listen carefully to this extraordinary chiming watch.

3 comments

I actually find it more legible than people say, but even if I could not tell the time, just being able to listen to it every quarter hour would be worth it

Not remotely qualified to judge this level of watch, but wow. Magnificent bit of unnecessary human genius right there

Price is just bananas but that does not stop me from loving this thing. Looks like an explosion of parts on the wrist in the coolest possible way