Intel’s Fab Problem Isn’t Money – It’s Empty Capacity. Pat Gelsinger’s Warning Still Stands

Throwing fresh capital at a chipmaker makes for dramatic headlines, but it doesn’t automatically translate into competitive silicon. That, in essence, is the point Intel’s former CEO Pat Gelsinger has been making as the company courts equity partners and government backing: none of it matters unless it fills the fabs. In other words, unless the money turns into sustained wafer starts from real, paying customers, you’re subsidizing buildings and power bills, not a durable foundry business.

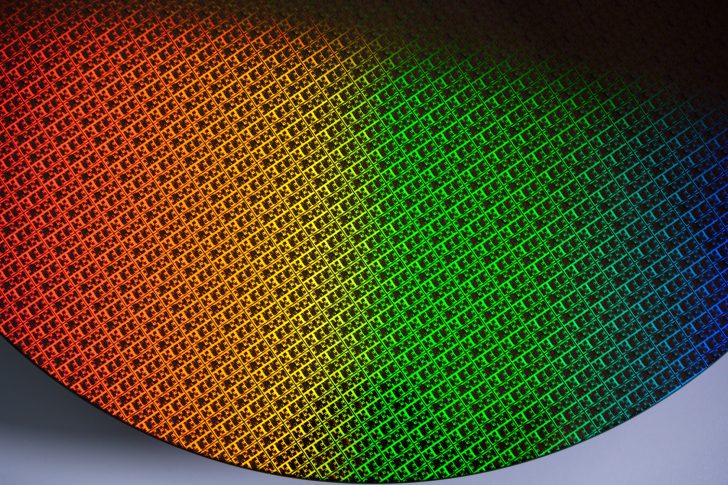

Gelsinger’s framing is blunt and useful: the only metric that ultimately matters is whether today’s deals cause more fabs to be built and kept busy in the United States. Market pops on announcement day are noise. Long-term fab utilization is signal. It’s also where Intel has struggled. Despite a string of equity-flavored arrangements and political tailwinds, none of the recent agreements have come with firm, public commitments to load Intel’s lines with high-volume designs from marquee customers.

Consider the optics. A U.S. government stake or incentive can nudge domestic companies to look Intel’s way. Talks with obvious anchor tenants – names like NVIDIA or AMD – naturally follow. Yet as of today, those conversations have not produced definitive foundry capacity bookings. The message between the lines of Gelsinger’s media hits is clear: influence isn’t the same as purchase orders, and national-industrial policy only works when it translates to tape-outs and multi-year take-or-pay contracts.

Why is this so crucial? Because fabs are not normal factories. They are capital furnaces. Every cleanroom, tool install, and process qualification pushes fixed costs skyward. The economics demand high, predictable utilization – think 70–90% – to keep per-wafer costs competitive. Leaving a cutting-edge node underfilled is like flying a widebody jet with ten passengers: technically possible, financially disastrous. That is why foundries chase pre-payments, capacity reservations, and co-development roadmaps. Without that, subsidies risk funding underused capacity.

Gelsinger has also been candid about Intel’s long rebuild. He has described the job as unwinding more than a decade of compounded missteps – slips in process technology, organizational drift away from technologist-led decision making, and messy operations that blurred the lines between the product P&L and the foundry mission. His five-year reconstruction timeline wasn’t PR; it was an admission that regaining process leadership is a grind. The recent progress around Intel’s 18A process – packaging advances, design enablement kits, and the first wave of internal and external test silicon – marks real momentum, but a milestone is not a market. The scoreboard will be counted in third-party tape-outs that go to volume on Intel lines.

Policy has been both accelerant and irritant. The CHIPS Act set out to catalyze domestic manufacturing, and Intel was an obvious beneficiary. Yet timing matters: delays in disbursing funds and the friction of compliance added to program risk just as rivals extended their leads. Gelsinger’s disappointment with the pace wasn’t personal theater; every quarter of slippage in tool orders or ramp schedules compounds into calendar years at the bleeding edge. Even so, public support is now real and sizable. The catch – again – is that subsidies should be bridges to commercially validated demand, not crutches for idle square footage.

So what would “filling the fabs” actually look like? Three things. First, anchor customers – at least one top-five chip designer committing meaningful wafer starts on an advanced Intel node, underpinned by co-optimization agreements. Second, a design pipeline that broadens beyond a single flagship: CPUs, accelerators, networking ASICs, automotive and industrial controllers, each mapped to the right node and package. Third, contracts with teeth: multi-year, volume-indexed deals that give Intel predictable utilization and give customers predictable yields, roadmaps, and pricing.

Skeptics will ask: why would the likes of NVIDIA or AMD move away from the incumbents? Switching a foundry isn’t like switching cloud VMs. It touches RTL, libraries, compilers, DFM rules, IP availability, packaging, and supply-chain muscle memory. The answer is that serious designers will follow the best total platform: node competitiveness, packaging (e.g., advanced 2.5D/3D integration), predictable yield learning curves, and geopolitically diversified risk. If Intel can demonstrate sustained parity or leadership on any given vector – and guarantee capacity when others are constrained – then portfolio diversification becomes rational, even attractive.

This is where Intel’s internal product and external foundry stories intertwine. Critics like to say, “Be a world-class foundry or a world-class designer, not both.” The counterpoint is that integrated device manufacturers can prove their nodes with in-house silicon, compressing learning loops and showcasing reference designs – if the organizational boundaries are crisp. That means ruthless accounting (internal customers pay market-realistic prices), clear roadmaps, and a foundry culture that treats every external client as a first-class citizen. It also means shipping competitive products in the market to build credibility that the process is real, not PowerPoint.

Gelsinger’s larger indictment – that Intel lost technical leadership for too long – shouldn’t be controversial. The question is whether the current leadership can translate hard-won 18A milestones and packaging prowess into repeat business from the industry’s most demanding buyers. Equity deals and federal partnerships extend the runway. But the plane must still take off, and that requires load factor.

There’s a constructive path forward. Lock down two or three lighthouse customers with staggered tape-outs. Publish transparent PDK maturity metrics and third-party IP availability timelines. Openly report yield-learning curves and cycle-time improvements. Expand the catalog of chiplets that can be mixed and matched on advanced packages. And keep the U.S. incentives tied not just to groundbreaking ceremonies but to verifiable production output and job creation.

The bottom line echoes Gelsinger’s refrain: money is table stakes, not checkmate. The scoreboard will be written in wafers started, dies shipped, and designs renewed. If the latest deals ultimately fill the fabs, they’ll be remembered as the turning point. If they don’t, they’ll be footnotes to a bigger story about how hard it is to buy your way back to leadership in semiconductors.

1 comment

Gelsinger’s right about the 5-year rebuild. They lost the plot for a decade; clawbacks take time